Cristina: Come è noto, l’origine del nome no-man deriva da una frase storica tratta dal poema dal titolo “No Man is an Island”, del poeta e saggista inglese John Donne, scritto nel 1624 e che purtroppo è quanto mai attuale e torna ciclicamente ad essere di ispirazione per le contingenti situazioni socio-politiche. La stessa PJ Harvey a giugno 2016, ospite al festival olandese “Down The Rabbit Hole”, nel bel mezzo della sua performance recitò la poesia di Donne proprio in risposta all’esito delle votazioni del referendum Leave or Remain sulla Brexit. No-man quindi racchiude in sé un significato assolutamente emblematico a nostro parere dei tempi storici che stiamo attraversando, confermando purtroppo che la divisione tra esseri umani forse è sempre più palese ed evidente. A tal proposito vogliamo chiederti se, a tuo parere, nella società e nel momento attuale, credi ancora che la musica possa rendere ognuno di noi meno un’isola, e in che modo.

Tim: Bene, hai iniziato con una domanda seria! Penso tu abbia ragione. Viviamo in tempi sempre più divisivi e non credo che si tratti solo di Brexit o Trump. Ci sono molte altre questioni, dal conflitto israelo-palestinese e così via. Sembra che sia molto difficile mantenere, in particolare in questa ‘era dei social media’, un dialogo articolato, ragionato ed equilibrato in cui le persone si possano ascoltare reciprocamente. Ciascuna parte di una discussione ritiene che la propria posizione sia ben formulata. Non mi piace necessariamente essere divisivo, ma vedo persone di entrambe le parti comportarsi in modo spaventoso e scrivere in modo incredibilmente aggressivo. Ad esempio, c’è un giornalista di sinistra molto rispettato – che mi piace ma non menziono – che regolarmente lancia insulti ai politici, il che non fa altro che alimentare la rabbia e il pregiudizio, mentre in realtà dovrebbe esserci un’analisi dettagliata del motivo per cui questo è un atteggiamento sbagliato da avere. Penso che ciò sia dovuto alla natura dei social media. Qualunque sia la ragione, sembra che un discorso ragionevole da entrambe le parti non sia possibile e non sia benvenuto. E, in realtà, non biasimo le persone per il fatto di non provarci perché, quando ci provano, vengono criticate dalla loro stessa fazione per non aver insistito con la forza che avrebbero dovuto, e vengono criticate dall’opposizione per aver avuto la temerarietà di non essere d’accordo. Quindi penso che la natura della discussione politica sia diventata quasi insostenibile al giorno d’oggi. A questo proposito, in un certo senso, a volte ho scelto questa opzione di rifugiarmi nella bellezza.

C’è uno dei primi testi dei no-man che si collega al cofanetto, è un lato B di Lovesighs scritto tra il 1990 e il 1991, che racconta il caos urbano fuori dalla stanza in cui abita questa persona che, dal momento che sente che la sua voce è troppo debole, si sta ritirando nell’arte: musica, letteratura, film. Devo dire che a volte mi sento colpevole di questo, adesso, che sento che la mia voce ha così poco peso, e poiché non voglio essere parte di quel feroce disaccordo da entrambe le parti, in un certo senso sento di perdermi nella bellezza della musica o nella fantasia di un libro, in parte per fuggire. Spero davvero che la musica, la letteratura e il cinema possano ancora essere una sorta di guarigione che unisce le persone. Sono davvero fortunato per il fatto che quando incontro i fan ai concerti o quando parlo con loro online, in generale, non entriamo in dibattiti politici, ma entriamo invece in discussioni dettagliate ed entusiaste su cosa significhino le canzoni per noi o cosa l’arte può significare per noi. Quindi in un certo senso stiamo aggirando i problemi, ma spero che sia un fattore unificante nonostante il mondo in cui viviamo. L’unica altra cosa che direi per proseguire è che, ovviamente, dobbiamo vivere come se nessuno fosse un’isola, non possiamo vivere senza essere consapevoli del caos politico che ci circonda, quindi trovo che che dal punto di vista dei testi, anche quando non ne sono consapevole, queste cose trapelino nelle canzoni. Non puoi fare a meno, in quanto essere umano nel 2023, di essere colpito dalla disumanità che vedi intorno a te.

Cristina: Sono completamente d’accordo con te e penso che lo sia anche Marco. Per il fatto stesso che siamo qui, crediamo che la musica possa ancora fare la differenza, in qualche modo.

Marco: E a proposito di arte in tutte le sue forme, la foto di copertina del cofanetto Housekeeping è molto bella, in linea con lo stile degli album dei no-man, ma allo stesso tempo è qualcosa di nuovo. Penso che sia opera di Carl Glover, ma vorrei chiederti come siete arrivati a quell’immagine.

Tim: È interessante, perché varia da disco a disco. Per alcuni avevo un’idea molto forte della copertina. Sapevo esattamente cosa volevo per le copertine di Flowermouth, Returning Jesus e Dry Cleaning Ray

e Carl Glover le ha rese realtà. Ma poi, per esempio, quando ho descritto il concetto dietro Together We’re Stranger, lui stesso ha ideato quell’immagine, ed è una delle mie copertine dei no-man preferite, poiché incapsula perfettamente i testi e l’atmosfera, pur essendo questa anche una visione piuttosto fresca e astratta della cosa.

D’altro canto, sia io che Steven sapevamo cosa volevamo per Love

You to Bits. Ed è stato interessante, perché ci sono voluti duecento tentativi per ottenere la copertina che volevamo. Non credo che Carl abbia mai impiegato più tempo, e la cosa strana è che sapevamo in modo molto specifico cosa volevamo. Penso che Carl abbia probabilmente tratto molte copertine per i The Pineapple Thief e i Marillion dalla pila degli scarti di Love You to Bits, perché erano copertine davvero buone. Semplicemente non era quello che pensavamo, articolato nella musica o nei testi.

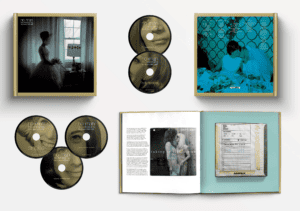

Per Housekeeping Carl aveva le mie note di copertina, quelle di Matt Hammers, l’elenco dei brani e il titolo. Quindi ha inventato una serie di variazioni, e questa volta penso che invece di duecento ne abbia prodotte circa diciotto. Per una di queste, sia io che Steven abbiamo immediatamente pensato: “Okay, c’è una sorta di qualità inquietante, che in un certo senso riflette la sensazione di alcuni dei primi lavori dei no-man”. Quindi tutto si è sviluppato da lì, in effetti. Abbiamo trovato un’immagine che ci è piaciuta e che ci ha portato a molte altre immagini e poi al cofanetto, che ovviamente contiene molte fotografie d’epoca, matrici di biglietti, poster e così via. Quindi, questa copertina deriva più dal punto di partenza di Carl che dal nostro punto di partenza, ma tutti noi abbiamo contribuito al modo in cui appare il cofanetto nel suo insieme.

Cristina: Oltre al cofanetto Housekeeping, uscirà anche Swagger. Puoi dirci qualcosa a riguardo? Perché pubblicare entrambi i prodotti contemporaneamente? C’è un risparmio se acquistati insieme?

Tim: Avevamo finito il cofanetto molto tempo fa, probabilmente circa un anno e mezzo, o due anni fa. L’artwork, il cofanetto, il mastering, tutto era pronto, ma è stato sospeso perché Steven stava pubblicando i suoi album e poi quello dei Porcupine Tree. La cosa bella di Swagger è che non ce lo aspettavamo. È successo in modo del tutto spontaneo, probabilmente solo tre mesi fa, quando ho ascoltato alcuni brani di quel periodo. Ho parlato con Steven e ho detto “Vedi, sono davvero ottime canzoni”. E Steven, nei giorni successivi, mi ha detto: “Sai, avevamo scritto questo e quest’altro nello stesso periodo”, e ha portato alla luce circa 40, 50 minuti di musica, alcuni dei quali avevo completamente dimenticato. C’è un pezzo che è un’improvvisazione tra me e Steven, direttamente su cassetta, era adorabile e ho pensato: “Come l’abbiamo fatto? Quando l’abbiamo fatto?” Ed è così che sono venuti fuori i brani di Swagger. Così, all’improvviso, entrambi stavamo ascoltando di nuovo brani che avevamo scritto nel corso di un anno e che non abbiamo mai realmente documentato, perché, quando i no-man si sono formati per la prima volta, erano molto eclettici. Steven ed io avevamo gusti molto diversi, e la musica spaziava da pezzi davvero brevi e incisivi con una sorta di elemento funk o post-punk, a ballate epiche di sette minuti e mezzo, a pezzi con una qualità quasi progressive o psichedelica, o ai pezzi presenti su Speak.

L’album Speak è qualcosa da cui eravamo ossessionati, una sorta di territorio senza tempo, quasi cantautorale. Entrambi amavamo molti cantautori degli anni ’60 e dei primi anni ’70, persone come Nick Drake, John Martin, Sandy Denny, Nico, e amavamo anche molta della musica di quel periodo in cui ci siamo incontrati per la prima volta, con artisti come i Cocteau Twins e i Dead Can Dance che producevano questa musica davvero bellissima, quasi senza tempo. E quindi Speak era, forse, spero, la nostra versione distintiva di ciò. In quel periodo, tuttavia, stavamo ancora scrivendo canzoni rock davvero violente e ballate epiche.

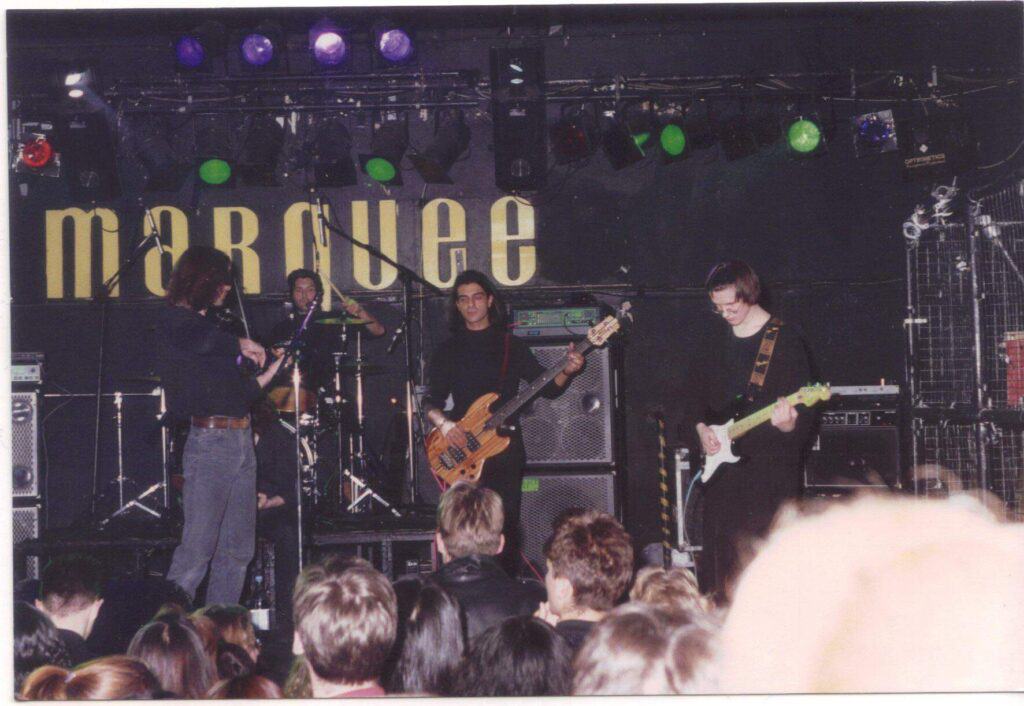

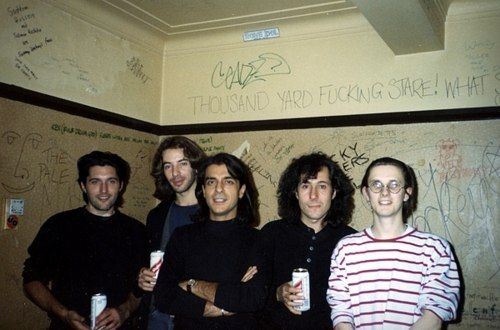

Abbiamo prodotto ‘Colors’ nel 1990, abbiamo firmato il contratto e da lì in poi è tutto ben documentato. Ma ciò che non è documentato è quel periodo tra Speak e ‘Colors’, quando facevamo musica con lo scopo di suonare dal vivo. Suonavamo a Londra e Manchester, e anche se non avevamo un contratto con una casa discografica, stavamo costruendoci un pubblico e attirando persone che venivano a vederci come band dal vivo. Stavamo scrivendo la musica per quelle esibizioni dal vivo, che erano davvero emozionanti. Devo dirlo, mi manca ancora adesso. Eravamo io, Steven e Ben, e noi tre eravamo quasi come tre frontman sul palco, piuttosto dinamici. Stavamo lavorando con dei nastri di accompagnamento, ma era tutto molto vivo e molto spontaneo. Quindi Swagger raccoglie la musica che avevamo scritto e registrato durante quel periodo, che non è mai stata pubblicata adeguatamente. Va dall’estate del 1989 all’estate del 1990, subito prima di ‘Colors’, che è molto diverso. Swagger cattura davvero un lato davvero insolito e unico della band. La maggior parte è in una modalità più elettronica, ma è anche più influenzata dal rock, a causa dell’elemento live.

La cosa interessante è che è venuto fuori quasi come il primo album che non abbiamo mai pubblicato, perché funziona davvero coerentemente come un unico disco, allo stesso modo di Speak. Probabilmente abbiamo ancora un’altra ora di materiale, che però è abbastanza diverso. È stato molto emozionante, perché tutto è accaduto molto velocemente. Abbiamo pensato: “Dio, è proprio bello!” ed è per questo che lo stiamo pubblicando. Swagger viene pubblicato dall’etichetta Burning Shed, come una sorta di uscita fatta in casa, mentre il cofanetto viene pubblicato dall’etichetta originale che ha pubblicato quel materiale, la One Little Indian. Sono venuti alla luce in due momenti diversi e ovviamente è stato incredibile mettere insieme qualcosa così rapidamente. Entrambi ci siamo sentiti davvero emozionati e abbiamo scritto delle note di copertina, quindi la cosa bella è che è stato creato nello stesso modo in cui lo era stata anche la musica. È stato abbastanza rapido, a differenza della mia spiegazione!

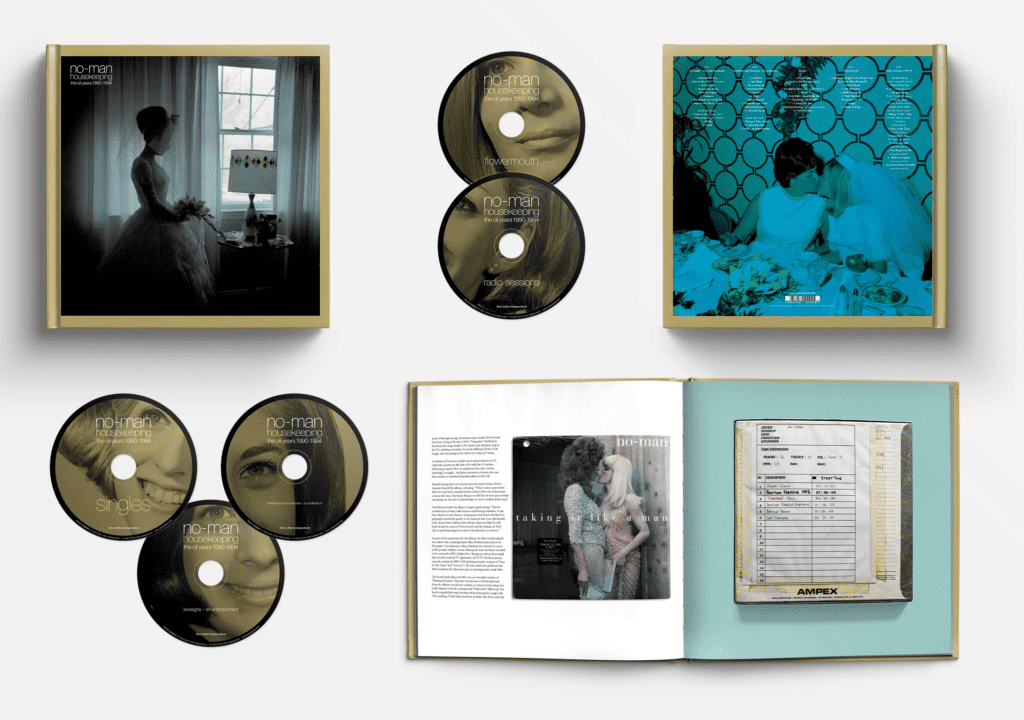

Marco: Cosa ci dici del cofanetto Housekeeping? Cosa contiene, oltre ai primi due album della band, Loveblows & Lovecries e Flowermouth?

Tim: C’è il materiale di Lovesighs, ovvero i singoli e le B-side del primo periodo, e un bel po’ di mix alternativi dalle sessioni di Loveblows & Lovecries. Sono ancora davvero soddisfatto di quel disco, mi è sempre piaciuto, e anche a Steven. Dato che non è mai stato ristampato, la gente ha sempre pensato che non ci piacesse, cosa che non è vera. La storia dietro l’album è particolare. Avevamo finito l’album nel 1992, e ho una versione definitiva con la copertina finita che solo io e Steven abbiamo. È la versione originale dell’album, ed è in realtà diversa al 50% da quella che alla fine venne pubblicata. Conteneva una versione più lunga di ‘Sweetheart Raw’, una versione molto più lunga di ‘Tulip’ e un mix completamente diverso di alcune canzoni. Mentre lo stavamo registrando, siamo andati in molti dei più grandi studi della Gran Bretagna. Usavamo studi molto grandi con ingegneri del suono importanti, persone che lavoravano con i The Shamen e Bjørk, che all’epoca erano nella nostra stessa etichetta. E, cosa interessante, quella versione dell’album fu rifiutata. La casa discografica disse che non ci sarebbe stato nessun singolo di successo. Ovviamente ne fummo un po’ seccati, inizialmente, ma tornammo indietro e registrammo qualche altro pezzo. A loro piacque molto ‘Only Baby’, che piaceva anche a noi, per quanto fosse una delle poche cose che avevamo scritto con l’idea di comporre un singolo in mente. Abbiamo rimodellato l’album attorno a ‘Only Baby’: abbiamo creato un’introduzione orchestrale e abbiamo ripensato il resto dell’album. Abbiamo tolto un paio di pezzi, ne abbiamo inseriti altri, e poi abbiamo avuto la certezza delle nostre opinioni. Nella versione originale, ad esempio, c’era una versione di ‘Painting Paradise’ che avevamo registrato in un enorme studio con tantissimo riverbero. L’abbiamo ascoltata e abbiamo pensato: “Non siamo noi”, e così abbiamo scelto invece il demo che avevamo registrato nello studio di Steven. Se guardate i crediti della versione finale di Loveblows & Lovecries, molte di quelle tracce sono state registrate nel nostro studio di casa. Quindi, alla fine, la seconda versione dell’album uscita nell’estate del 1993 è quella che pensavamo fosse migliore. Abbiamo incluso in questo cofanetto alcuni mix alternativi della prima versione, così le persone possono decidere se eravamo matti o no. Poi ci sono le sessioni radiofoniche che abbiamo fatto alla BBC, sia acustiche che elettriche. C’è Colin Edwin che suona il contrabbasso in cinque o sei brani e Chris Maitland che suona la batteria in uno. Ovviamente Chris è un grande batterista, ma tutto ciò che fece in questa sessione radiofonica acustica dal vivo è colpire un piatto [ride], e se andava fuori tempo, lo indicavamo e lo sgridavamo. C’è anche una registrazione di ‘Sweetheart Raw’ alla BBC Radio Five, che non è mai stata pubblicata prima. L’abbiamo eseguita con il batterista di una band chiamata Slab [Chris Baker], che piaceva sia a me che a Steven. Non l’avevo mai sentita finché non abbiamo lavorato al cofanetto. Infine, all’interno del box set troverete un saggio di Matt Hammers, un giovane americano che gestisce un blog dedicato ai no-man, poi un mio saggio, un piccolo saggio di Steven e anche molte fotografie dell’epoca.

Cristina: La nostra prossima domanda riguarda in realtà il booklet, sembra davvero interessante. Quanto è grande?

Tim: È un box set da 10×10 pollici, con cinque dischi e 64 pagine. Fondamentalmente abbiamo provato a ricomprare la musica dall’etichetta discografica, ma loro non hanno voluto; alla fine abbiamo lavorato in associazione, per produrre la cosa migliore e più bella che potevamo. Il libretto contiene di tutto, dalle prime recensioni a ottimi esempi di cassette a nastro e, non so come l’abbiano ottenuto, ma c’è uno dei miei fogli con i testi originali. Dagli anni Novanta in poi ho sempre usato il computer o l’iPhone quando scrivo testi, ma qui c’è una specie di pezzo scritto a mano che probabilmente avevo lasciato a Steven e lui ha conservato. E visto che siamo qui, ho trovato anche il vinile originale di Loveblows & Lovecries [Tim ci mostra il vinile].

Marco: Tim, hai detto che l’etichetta non voleva che compraste i diritti delle canzoni. Vale solo per Loveblows & Lovecries o anche per Flowermouth? [La domanda sorge perché, anche se non ci sono state nuove uscite per Loveblows & Lovecries, nel corso degli anni i no-man hanno effettivamente ristampato Flowermouth su KScope]

Tim: Possiedono tutto loro, dal 1990 al 1994, quindi Lovesighs, Loveblows & Lovecries e Flowermouth. Fortunatamente hanno voluto ripubblicare questo materiale e ci hanno lasciato lavorare in collaborazione con loro, e penso che anche loro ne siano davvero contenti.

Marco: Hai già detto che le note di Housekeeping sono state scritte da Matt Hammers, un giovane autore che nel suo blog ‘All the Blue Changes’ ripercorre l’intera storia dei no-man intervistando i suoi protagonisti. Cosa ti ha colpito del suo lavoro, al punto da chiedergli di lavorare sul cofanetto?

Tim: Fondamentalmente, Matt mi ha contattato tramite il blog e sono rimasto colpito dalla sua ossessiva attenzione ai dettagli. È fantastico, perché abbiamo già avuto siti di fan di no-man in passato, penso che ci sia un sito polacco e anche Tony Kinson ha realizzato un eccellente sito per molti anni, quindi è stato bello vederne un altro. Era davvero ben progettato e Matt sembrava avere un entusiasmo genuino e una vera attenzione ai dettagli. Quindi in un certo senso ho ammirato la natura delle domande che mi stava ponendo e mi è sembrato che, poiché ha fatto così tanto lavoro sul sito, se lo meritasse. Era un modo per ringraziarlo per quello che ha fatto, perché amiamo la musica e, ovviamente, apprezziamo quando quell’amore viene mostrato da altre persone.

Marco: Soprattutto da parte dei giovani, credo. Quanto è importante per te aver raggiunto anche una generazione di ascoltatori più giovani?

Tim: Beh, è fantastico. Voglio dire, in un certo senso non accade più così spesso come prima. Ricordo quando ascoltavo musica da adolescente. Gran parte di ciò che ascoltavo era stata composta da persone più giovani di me o di qualche anno più grandi di me, ma ero sempre interessato, diciamo, agli artisti jazz che avevano trenta o quaranta anni più di me o artisti rock che ne avevano venti più di me o giù di lì. Immagino che la mia generazione di ascoltatori sia molto consapevole delle generazioni di musicisti che ci hanno preceduto e di quelle successive. Per quanto la musica sia ormai più onnipresente di allora, non sembra esserci altrettanto ascolto intergenerazionale. È davvero importante e gratificante quando anche le persone più giovani capiscono o sentono questa musica. Il fatto che Joni Mitchell abbia vent’anni più di me non significa che non ascolti appassionatamente la sua musica, perché lo faccio.

Cristina: Secondo te, quali sono stati i passi più importanti che vi hanno permesso di firmare con la One Little Indian in quel periodo? Probabilmente la cover di ‘Colors’ di Donovan? E inoltre, perché avete scelto di reinterpretare questa canzone del 1965?

Tim: Credo tu abbia ragione, in sostanza; ne parlo un po’ nelle note di copertina di Swagger. Suonavamo a Londra. Entrambi eravamo incredibilmente ambiziosi. I no-man si stavano costruendo un pubblico. Suonavamo in locali decenti come il Marquee, molto rinomato, il 100 Club, il Rock Garden e il Borderline a Manchester; eravamo sugli stessi palchi in cui suonavano band allora emergenti come gli Oasis e i Blur. Stavamo creandoci un pubblico e la cosa positiva era che quando suonavamo, venivamo richiamati e avevamo più pubblico della volta precedente. Nonostante ciò, non stavamo ottenendo nulla, e io mi ero trasferito a Londra per essere più vicino a Steven in modo da poter prendere la band più seriamente. Nell’estate del 1990, nonostante le cose andassero bene per noi, non riuscivamo a ottenere la presenza ai concerti di giornalisti o di rappresentanti di case discografiche. Così sono tornato a casa, nel nord-ovest dell’Inghilterra, tra Manchester e Liverpool, e ho avuto modo di leggere che gli Happy Mondays avrebbero fatto una cover di ‘Colors’ di Donovan. Ne ho parlato con Steven, perché a entrambi piaceva molto Donovan, e avevamo già fatto almeno una sua cover, ‘River Song’, che è su Speak, e gli ho detto: “Perché non registriamo anche noi, per scherzo, ‘Colors’ e la pubblichiamo prima che lo facciano gli Happy Mondays?” Sono andato a casa sua e abbiamo fatto una versione davvero inaspettata, perché abbiamo usato un campionamento hip-hop. Abbiamo anche incorporato il violino di Ben e pensavamo che la combinazione fosse davvero fresca e unica. Tutto era nato casualmente, quindi eravamo davvero entusiasti di ciò che era successo. Ed è stato davvero quasi come un ultimo tentativo disperato. Non stavamo andando da nessuna parte. Abbiamo registrato la cover e abbiamo pensato: “Facciamo semplicemente un singolo da 7 pollici”. Sapevamo che avremmo perso molti soldi, ma lo abbiamo fatto comunque. Date le caratteristiche della musica dei no-man, che è seria, ho scritto un comunicato pubblicitario comico e, avendo studiato attentamente i giornalisti che pensavo ci potessero apprezzare, abbiamo inviato loro cinque copie del singolo. È stato incredibile. Steven mi ha chiamato e ha detto: “Sai che siamo il singolo della settimana su Melody Maker?”. E così, dal nulla, ci siamo ritrovati il singolo della settimana su Melody Maker, il singolo della settimana su Sounds, il singolo della settimana sul televideo di Channel 4 Television. Oggi sembra pazzesco, ma il televideo era una cosa importante all’epoca. Le battute sono andate abbastanza bene, ma la musica è piaciuta ancora di più e nel giro di un paio di settimane i nostri concerti erano affollati da personaggi delle case discografiche, giornalisti e così via. Era interamente merito di ‘Colors’. In particolare c’era un giornalista, un certo Chris Roberts, che adorava la band, e venne al concerto successivo, fu un sostenitore da allora ed è stato davvero importante per noi. Curiosamente, nello stesso periodo, i The Shamen ci sentirono e gli piacemmo molto, perciò furono così gentili da fare un remix per i no-man gratuitamente per poi raccomandarci alla loro etichetta discografica. Così, in un paio di mesi tutto si concretizzò per noi.

Marco: Loveblows & Lovecries contiene alcuni dei brani più accessibili della carriera della band e della tua, mantenendo inequivocabilmente lo “stile no-man”. Ascoltandoli ora, trent’anni dopo la sua pubblicazione, quali tratti pensi siano ancora evidenti nel vostro suono?

Tim: Penso che ci siano certe sequenze di accordi e texture verso cui entrambi gravitiamo. Ad esempio, avete ascoltato The Harmony Codex, che è probabilmente il mio album preferito di Steven e probabilmente quello che a tratti si è avvicinato di più ai no-man. Curiosamente, Steven ha mixato i miei album, ma il mio nuovo album, che uscirà l’anno prossimo, è il primo in cui ho scritto e suonato da solo l’intero lavoro. Ciò che è interessante è che alcuni brani potrebbero appartenere ai no-man. Quello che è stato strano è che Steven in quel momento lavorava sul suo album solista, io scrivevo da solo a mia volta, e ci sono brani in entrambi gli album che potrebbero appartenere ai no-man. C’è una sorta di dolcezza amara, nel descrivere ciò che tu chiami con la parola “accessibile”. Penso che il miglior materiale dei no-man, secondo me, riesca ad essere abbastanza emozionale, ma non travolgente. Ha una specie di accattivante sensibilità agrodolce che penso ci sia sia in The Harmony Codex, sia nel mio album, e so che c’è anche in Loveblows & Lovecries. Vi è una certa armonia ricca e un nucleo che credo continuiamo a cercare naturalmente, continuando a gravitare verso questa sensazione nella musica. Alcune delle cose migliori che facciamo come no-man sono tali perché mi piace la musica sperimentale e mi piace la musica accessibile, ma alla fine – e Steven la pensa allo stesso modo, forse è per questo che i no-man sono i no-man – mentre reagiamo entrambi ai King Crimson più estremi o a Stockhausen, allo stesso tempo reagiamo a un certo pop puro, che siano i Pet Shop Boys o i Beach Boys. Penso che ciò che i no-man riescono a fare sia quasi sintetizzare questi elementi in qualcosa di abbastanza ascoltabile e accessibile nonostante le influenze da entrambi i lati. Se da solo, a volte, posso oscillare tra il rumore estremo e il pop estremo, penso sempre che, quando scrivo con Steven come no-man, ci bilanciamo a vicenda per qualche motivo. Penso che questo sia ciò che contraddistingue i no-man, e penso che si senta. E non sto dicendo che siamo come questo artista o siamo bravi come quest’altro, ma penso che ci siano altri artisti che possiedono questa qualità, che io considero “mainstream creativo” e sono abbastanza accessibili ma non risparmiano sperimentazioni e non sono disonesti emotivamente. Dark Side of the Moon dei Pink Floyd e Hounds of Love di Kate Bush sono ottimi esempi di ciò; Laughing Stock dei Talk Talk, A Walk Across the Rooftops di The Blue Nile e più recentemente, penso, anche Bjørk ha fatto lo stesso, e persino gli Elbow sono riusciti a produrre musica che è bella, interessante e riesce anche a comunicare naturalmente. Penso e spero che questo sia quello che abbiamo fatto come no-man: sintetizzare in qualche modo l’estremo dei nostri gusti. E qua si torna alla conversazione che stavamo avendo prima sugli estremi della politica, se la musica può passare e essere una voce unica. Forse è questo che fa, è un dialogo che produce qualcosa che mette in comunicazione anziché allontanare.

Marco: Penso che un buon esempio di ciò che hai detto sia il brano che Jansen, Karn e Barbieri suonarono in Loveblows & Lovecries, ‘Sweetheart Raw’, con la lunga parte strumentale e stratificata alla fine.

Tim: Quel brano è stato interessante da scrivere, perché è iniziato come un paio di vecchie canzoni, quando non avevo ancora il mio studio casalingo e scrivevo un po’ alla chitarra. Quindi quel brano è iniziato come una sorta di pezzo acustico cantautorale a quattro accordi che ho suonato a Steven, e ciò che rimane di quello è il ritornello. Improvvisamente, qualcosa di diverso è capitato in studio quando abbiamo coinvolto Jansen, Karn e Barbieri. Ha preso completamente un’altra vita. Curiosamente, con quel brano, riesco anche a sentire alla fine, in quella sezione dove “va via” musicalmente, la nascita dei primi Porcupine Tree più space rock.

Marco: Concordo pienamente. E parlando di quelle tre persone estremamente importanti per te – Jansen, Barbieri e Karn – quando ho sentito che stava arrivando questa raccolta, ho pensato che potesse contenere una performance dal vivo con quella formazione. Quindi, questa è una domanda da fan puro: esiste davvero? Se sì, la sentiremo?

Tim: Purtroppo no, penso che le uniche cose di buona qualità di quel periodo siano un paio di registrazioni con altri musicisti dalle sessioni alla BBC. Ma, per qualche motivo, non abbiamo una registrazione live adeguata. L’unica cosa che abbiamo sono cassette davvero pessime registrate davanti al palco con la voce e la batteria distorta e che suonano orribili oltre ogni immaginazione. Che tristezza. Ma abbiamo potuto fare molte registrazioni in studio, quindi io e Steven abbiamo continuato a scrivere durante quel periodo. C’è molto che non è stato pubblicato, e potremmo pubblicare in qualche momento futuro alcuni dei brani: ‘Angel Gets Caught in the Beauty Trap’ ne è un esempio. Ci sono voluti quattro anni per completarla. È iniziata, fondamentalmente, con me e Steven con la sola sezione di apertura, probabilmente i primi due minuti e mezzo, che pensavamo funzionasse davvero bene. Poi Steven sentiva che potevamo portarla ancora più avanti, come sarebbe successo alcuni anni dopo con ‘Lighthouse’ [traccia di Returning Jesus, del 2001, i cui primi minuti furono composti durante le sessioni di scrittura di Flowermouth]. E così sono andato da lui una sera e abbiamo ampliato il demo di due minuti e mezzo fino a qualcosa come venti minuti, forse anche più lungo, più elettronico e minimalista della versione che è stata pubblicata. Poi, occasionalmente, durante quel periodo prima di aver firmato il contratto, la suonavamo dal vivo. Quindi ci sono delle registrazioni dal vivo molto belle di quel brano, del 1989, che per qualche motivo sono ben registrate, a differenza delle cose con Jansen, Barbieri e Karn. Inoltre, ci sono tutte le versioni: c’è una versione di otto minuti del 1992 che ho sentito di recente, che non ha Robert Fripp e Ian Carr ma funziona comunque molto bene; c’è una fantastica versione di cinque minuti e mezzo, che ho quasi pensato di includere in Swagger, perché cattura questo periodo tra le fasi. Fondamentalmente si tratta di me e Steven, in una stanza, fortunatamente ben microfonata, mentre la stiamo suonando per la prima volta a Ben. La parte iniziale è la sezione della canzone che abbiamo composto, che si sviluppa e Ben sta improvvisando e fa una bellissima parte. Verso la fine io improvviso e canto in modo molto più aggressivo, quindi finisce quasi in uno stile dinamico alla Peter Hammill o Michael Gira degli Swans.

Marco: Penso che ‘Angel Gets Caught..’ sia nella lista ristretta delle mie canzoni preferite di tutti i tempi. Riassume abbastanza bene come canzone quello che hai detto prima: è una canzone di 11 minuti, ma è piuttosto intima, abbastanza accessibile in un certo senso, e naturalmente c’è il lavoro di tutte le altre persone coinvolte che è stato incredibile.

Cristina: Ho qualcos’altro da dire su ‘Angel Gets Caught…’. Mi piace, a volte, pensare a quale sia il momento perfetto in una canzone che sto ascoltando, anche se è lunga come questa. In questa, per me, accade al terzo minuto, quando la tromba di Ian Carr entra in scena. Sono rimasta rapita da questo momento perfetto, bello e sublime.

Tim: Penso che tu abbia ragione, con alcune canzoni ci sono momenti perfetti in cui può essere solo una nota della tromba o una nota della chitarra. Anche io sono un grande fan del brano, e le performance di tutti sono state superlative. Mi piace molto anche ‘Simple’ da Flowermouth, in parte perché inizia quasi come una canzone pop innocente e semplice, ma i testi diventano più complessi e la musica si fa più complicata man mano che procede. Quando eravamo in studio a produrre quella canzone, Robert Fripp stava creando frammenti di magia qua e là e con quel brano si è proprio perso ed ha costruito quasi una sinfonia di chitarre soundscape su tutto il pezzo, che è poi come è finito il brano sul disco. Quindi è stato un tipo di magia che è accaduta in tempo reale. Ed è stato anche fantastico lavorare con persone come Mel Collins e Ian Carr. E, naturalmente, percepisco quel momento anche con la musica degli altri, quando ti piace la canzone e improvvisamente, potrebbe essere solo un particolare sax, tromba o chitarra che colpisce un’armonia e ti porta ad amare la canzone fino a farla diventare una delle tue canzoni preferite di tutti i tempi, perché quel momento ti riempie di qualcosa.

Cristina: Una cosa affascinante su Flowermouth è come sia stato respinto dall’etichetta nonostante la partecipazione di tutte le leggende della musica che abbiamo già menzionato. L’idea che queste leggende supportassero il vostro modus operandi è stata importante nel farvi continuare sulla vostra strada senza tenere conto delle richieste dell’etichetta One Little Indian?

Tim: Come ho detto, nel primo album giravamo per grandi studi, ma poi abbiamo capito che spesso preferivamo quello che avevamo fatto nel nostro studio. Con Flowermouth, abbiamo pensato: “Potremmo non avere mai più un’altra opportunità per fare un disco, quindi facciamolo il migliore, il più grande, il più bello possibile”. In altre parole: “Lavoriamo con le persone con cui vogliamo lavorare, facciamo la musica che vogliamo”. Di tanto in tanto, affittavamo uno studio esterno solo per registrare Mel Collins o Ian Carr, poiché era più facile per loro, ma è stato quasi esclusivamente fatto allo studio no-man’s land. L’etichetta non era coinvolta, mentre per il primo album venivano alle sessioni di registrazione e ci dicevano cosa pensavano sarebbe dovuto accadere, che li ignorassimo o meno. Per questo album abbiamo completamente ignorato tutti e abbiamo prodotto ciò che volevamo produrre. Avevamo un budget leggermente più piccolo per questo e l’abbiamo speso tutto nel nostro studio casalingo. Abbiamo comprato ottimi microfoni, un grande registratore ADAT; abbiamo pagato Robert Fripp e Ian Carr. Abbiamo pensato: “È qui che andrà il denaro questa volta, non in un grande studio”. Poi noi e il nostro manager – avevamo il manager dei Talk Talk in quel momento – abbiamo presentato l’album all’etichetta, alla quale è piaciuto molto il brano ‘Watching Over Me’, che è un altro di quei pezzi che ho portato come un semplice strimpellare acustico, come ‘Teardrop Fall’, in realtà. Ci sarebbe dovuto essere un singolo e un video per ‘Watching Over Me’, Mike Bennion aveva già fatto una sceneggiatura apposita. Poi il nostro manager è andato in vacanza e una volta che l’etichetta ha metabolizzato l’album – specialmente gli undici minuti di ‘Angel Gets Caught…’ – hanno pensato: “Ok, avete avuto la possibilità di essere una band pop e avere successo. Non avrete mai successo con questo” e per risparmiare sul budget hanno ritirato l’idea del singolo e del video. Ironia della sorte, Mike ha poi utilizzato l’idea per la BBC 2 Television. Probabilmente l’avete vista anche voi sulla TV italiana, a volte erano molto creativi, con animazioni intelligenti tra i programmi. Quindi Mike ha riutilizzato le sue sceneggiature, che aveva scritto per il video, e alla fine è diventata un’idea premiata. Una grande ironia è che, in parte a causa della qualità della musica, in parte a causa della qualità delle persone con cui stavamo lavorando, l’album ha venduto sei volte di più del primo album ed è andato abbastanza bene seppur con un minor budget rispetto al primo album. Quindi, alla fine fu un bel risultato e ci ha dato il coraggio di pensare “Ok, cosa vogliamo fare ora?”. Allo stesso tempo pensammo: “Se avessero fatto il video, se avessero fatto la promozione, se avessero creduto in questo album come noi ci credevamo, avrebbe potuto vendere dieci o venti volte di più, non solo sei”. E, contrariamente alla credenza popolare, non siamo mai stati abbandonati dalla One Little Indian. Volevano tenerci per Wild Opera, infatti c’è una cassetta white label di Wild Opera su One Little Indian. Il motivo per cui non siamo rimasti con loro è che il budget stava diminuendo sempre di più e, fondamentalmente, hanno ammesso che lo avrebbero soltanto pubblicato. Non avevano necessariamente entusiasmo per la musica, perché ancora una volta, ironicamente, avevamo prodotto questo sontuoso album che aveva fatto meglio del previsto e con cosa avremmo dovuto farlo succedere? Un disco davvero sperimentale, pieno di dissonanze e ritmi amari. Credo che non lo avrebbero promosso correttamente. Quindi siamo tornati alle basi e abbiamo firmato con una piccola etichetta indie che aveva già pubblicato delle band che ci piacevano, come Spaceman 3 e Bark Psychosis, e così via.

Marco: Rimanendo alle sessioni di Flowermouth, com’è stato avere Robert Fripp a suonare la chitarra nella camera da letto di Steven?

Tim: È stato incredibile. Penseresti che mi sia abituato a questo, perché ho lavorato con persone che ammiro. Da adolescente amavo Japan, i Talk Talk, i King Crimson, i Pink Floyd. E ci siamo ritrovati con il manager dei Talk Talk, a lavorare con Robert Fripp, Mel Collins e tante persone che ho amato crescendo. Era emozionante allora, e deve rimanere qualcosa di eccitante. Non devi essere cinico, ma non lasciarti neanche travolgere. La cosa che penso che a Robert piacesse di Steven e di me era che sapevamo cosa volevamo. Avevamo opinioni altrettanto forti quanto le sue, e scherzavamo. Quindi, da un lato, eravamo consapevoli di quanto fosse speciale, dall’altro non eravamo sopraffatti dalla sua presenza. Ma rimane comunque una grande emozione, perché ancora oggi lavoro con diversi artisti che ascoltavo da giovane. Ho lavorato con Kevin Godley dei Tennessee e Andy Partridge degli XTC ed è stato incredibile. Di recente ho lavorato un po’ con Julianne Regan degli All About Eve. È una cantante straordinaria e produsse un bellissimo singolo che ricordo di aver comprato quando ero più giovane. E mentre lavoriamo alla pari come creativi, penso ancora: “Dio, non è fantastico che sto lavorando con Julianne?” Ho lavorato con Robert Fripp in diverse occasioni perché è un musicista notevole, giustamente leggendario. Quello che è stato grande di lui e di Mel Collins è che, un po’ come Ben Coleman, li abbiamo lasciati liberi sulla musica. Io e Steven avevamo un’idea molto chiara di quello che volevamo. Il modo in cui lavoro con questi musicisti è che dico loro: “Questo è quello che voglio, dammi quello”; poi: “Dammi quello che pensi che questa traccia abbia bisogno”; e magari: “Improvvisa per divertimento”. E da questi tre approcci ottieni qualcosa. Ed è stato così che abbiamo lavorato con Fripp in particolare, ma anche con Mel Collins. La musica sgorgava da loro. Li mettevamo in qualsiasi situazione e andava bene. Subito suonavano intorno al brano. Non c’era imbarazzo. Ci davano quello che volevamo e poi suonavano in uno stile libero. È stata un’esperienza fantastica e molto speciale, e continua ad esserlo.

Cristina: Ci piacerebbe conoscere il processo creativo dietro alle canzoni, specialmente per quanto riguarda i testi. In questo processo trai ispirazione in qualche modo dalla letteratura? Qual è l’ultimo romanzo che hai letto e che ti ha particolarmente colpito?

Tim: Per quanto riguarda i testi, è una combinazione. Scrivo costantemente testi. Scrivo costantemente frasi, titoli, cose che mi vengono in mente e a volte suggeriscono sequenze intere. Ma tendo anche a scrivere le melodie quando compongo una canzone, che sia con Steven o da solo. La melodia e l’emozione devono venire prima, quindi, quasi come un poeta lavora entro il pentametro giambico, io lavoro entro la melodia che ho scritto. I testi tendono ad essere una combinazione di cose da cui attingo da anni e che improvvisamente scrivo sulle mie melodie e qualcosa ti afferra e sei catturato.

Per quanto riguarda “altri testi”, amo la letteratura, leggo ancora poesie e romanzi. Un libro che ho trovato molto interessante ed emozionante di recente è Termush di Sven Holm. Al momento sto rileggendo un libro di Kurt Vonnegut. Non è uno dei suoi migliori, ma ho comprato una nuova edizione economica perché la mia copia personale era completamente logora, e lo sto rileggendo per giustificare il suo posto nella mia collezione di libri. Sto anche leggendo un nuovo libro di Samantha Harvey chiamato Orbital. È quasi un resoconto poetico degli astronauti su una stazione spaziale, osservando la Terra e passando attraverso il processo di essere umani, le loro emozioni e i loro pensieri della vita sulla Terra. Ho sempre ammirato gli scrittori e intendo chiunque, da T.S. Elliot, Philip Larkin e Carol Pinter a Kurt Vonnegut e Raymond Carver. E in questo conto anche i parolieri. Joni Mitchell è una delle poche paroliere che è riuscita a trasmettere idee complesse ed emozioni ricche con un linguaggio abbastanza semplice ma poetico. Amo questa capacità e abilità di dire molto con pochissime parole. Penso che sia molto facile essere davvero pomposi, esagerati e grandemente eloquenti e usare polisillabi dopo polisillabi, ma penso che sia davvero difficile dire qualcosa di piuttosto profondo e significativo con pochissime parole. E certamente, per quanto riguarda i poeti britannici, Philip Larkin è uno di quelli. Ha un tale equilibrio, eppure potenza ed eleganza. In realtà c’è un poeta italiano, Giuseppe Ungaretti, che credo abbia una capacità simile di scrivere poesie totalmente belle e di farti andare in così tante direzioni con un linguaggio davvero abbastanza semplice. Ci sono scrittori che mi hanno influenzato nel corso degli anni e che continuo a leggere e che mi colpiscono ancora.

Cristina: Secondo te, non solo come compositore ma anche come ascoltatore di musica, perché una canzone può essere più apprezzata dopo diversi ascolti piuttosto che all’impatto iniziale? C’è una spiegazione “tecnica” o è semplicemente dovuto all’approccio individuale nei confronti di una canzone?

Tim: Penso che sia difficile e sì, molte delle cose che mi piacciono e amo non mi piacevano inizialmente, ma poi hanno iniziato a piacermi e mi hanno catturato. Penso che una delle ragioni per cui Dark Side of the Moon, Hejira di Joni Mitchell o i Beatles continuano a influenzare tanto sia perché ci sono tanti dettagli nei loro arrangiamenti, così tante armonie inaspettate e insolite, anche se a volte usavano solo quattro tracce. Come hai notato con ‘Angel Gets Caught…’, con Ian Carr, e il modo in cui suona “contro” gli altri strumenti; ma ci sono molte altre informazioni complesse in pezzi come questo, e forse lo amiamo abbastanza da ascoltarlo più e più volte. E poi, al cinquantesimo ascolto, pensiamo: “Oh, quel basso fa qualcosa che sorprende l’orecchio!” o “C’è un’armonia vocale che non avevo notato prima!”. Quindi penso che ciò abbia a che fare con il livello inaspettato di dettaglio e la natura emotiva umana, perché penso che quando si ascolta la moderna musica pop auto-tune delle classifiche è difficile provare un senso sorpresa, poiché ogni sorpresa è stata intenzionalmente eliminata, mentre in molta della musica di artisti come i Mercury Rev, i Flaming Lips, o Bjørk c’è ancora una qualità inaspettata nel compositore, ci sono così tanti dettagli nella produzione, che penso che ciò che emani è la fragilità umana, la natura del dettaglio e forse c’è anche un particolare sentimento che stiamo cercando che si riaccende quando li ascoltiamo.

Cristina: Sì, e ascoltare Flowermouth adesso è molto diverso che ascoltarlo vent’anni fa.

Marco: Tornando ai no-man, pensate che pubblicherete altri cofanetti o altro materiale inedito?

Tim: Spero che Swagger segni l’inizio di una serie di uscite d’archivio. Abbiamo sicuramente abbastanza materiale da giustificarle. E io e Steven parliamo sempre di registrare qualcosa insieme, quindi spero che ciò accada di nuovo. Più recentemente abbiamo parlato di registrare con il violinista originale, Ben, perché dopo così tanto tempo penso che potremmo riconquistare lo spirito di allora e farci qualcosa di diverso.

Marco: Ben ha suonato sia nel tuo ultimo album che in quello di Steven, giusto?

Tim: Sì, perché mi sono perso alcuni dei contributi che ha dato alla musica [dei vecchi no-man], e penso che ‘Dark Nevada Dream’ da Butterfly Mind [un brano dall’ultimo disco solista di Tim, in cui Ben suona il violino, n.d.r.] fosse quasi una direzione che i no-man avrebbero potuto prendere.

Marco: Quindi pubblicazioni d’archivio e forse nuova musica. Questa domanda in realtà viene da Evaristo, il fondatore del fan-club, che non ha potuto unirsi a noi oggi. Era al concerto alla Bush Hall nel 2008, quello che hai registrato per il DVD Mixtaped, ed è con quello che io ho scoperto la band. Chiede se c’è qualche possibilità di vedervi esibire di nuovo dal vivo qualche volta.

Tim: Di nuovo, io lo spero, ho suggerito un paio di cose a Steven, perché penso che lui sia stranamente meno entusiasta dell’idea di un tour adesso di quanto lo sia io. Mi esibirò in un paio di concerti in Inghilterra a gennaio, uno a Londra e uno nelle Midlands, a Kidderminster, e sul set proporrò per metà del materiale dei no-man e per l’altra metà dei miei lavori da solista. Penso ancora che ci sia molta vita in quel materiale dal vivo, e mi sento stranamente ancora più a mio agio nel produrre quella musica dal vivo ora di quanto non abbia mai fatto tra la fine degli anni Ottanta e l’inizio degli anni Novanta, quando avevamo quella formazione dei no-man a tre. Quindi ci spero, perché penso che l’ultima volta che abbiamo suonato insieme nel 2012 sia stato fantastico e non è stata una cosa ripetitiva. L’elemento veramente positivo dei no-man – e, spero, della musica che io e Steven produciamo – è che, anche se vogliamo essere fedeli al cento per cento all’emozione del materiale, non eseguiremo mai versioni fedeli nota per nota. La musica che suoniamo deve dare la sensazione di ciò che proviamo adesso ed evolvere con i nostri gusti. Il concerto a Bush Hall sembrava molto “in divenire” rispetto a quello che stavamo facendo nel 2011 e nel 2012, come se la band si fosse evoluta e noi ci fossimo evoluti come artisti, e la musica stesse assumendo una nuova vita. Sarebbe fantastico farlo di nuovo dal vivo.

Marco: Ti ho visto suonare con la tua band solista nel 2019 a Camden, dato che in quel periodo vivevo nel Regno Unito. È stata una serata davvero bella e i brani dei no-man erano davvero belli da ascoltare. Spero di vederti di nuovo sul palco, con Steven ed eventualmente Ben.

Tim: Beh, sai, l’ultima volta che ci siamo ritrovati insieme a suonare dal vivo è stato perché la mia band conosceva così tanto materiale dei no-man che Steven ha potuto unirsi a noi direttamente. Ed è lo stesso adesso, anche se ora sono con una band completamente diversa. Onestamente direi che, musicalmente, potrebbe essere la migliore band dal vivo con cui abbia mai suonato, e quello che stanno facendo con il materiale dei no-man lo sta reindirizzando e rimodellando. Penso che a Steven piacerebbe molto: verrà a vedere il concerto di Londra, e vedremo, forse avrà voglia di salire sul palco con noi, perché è quello che è già successo in passato. Quindi non è impossibile.

Cristina: E per quanto riguarda i concerti, se non sbaglio hai partecipato al concerto ‘Ships’ di Brian Eno a Londra, lo scorso ottobre. Ho assistito alla data di apertura a Venezia. Sono solo curiosa di chiederti cosa ne pensi dell’intero progetto e cosa pensi del contributo di Peter Chilver, che ha suonato le tastiere.

Tim: È stato fantastico, mi è davvero piaciuto. Ovviamente sono incredibilmente felice che Peter sia coinvolto in questo progetto. Sto ancora lavorando con Peter, è un musicista meraviglioso e un musicista molto sensibile e merita questo profilo. È stato bellissimo vedere qualcuno che meritava davvero di salire su quel palco. Nel complesso, è stato un concerto fantastico. Quello che ritengo interessante è che Brian ha settant’anni e avrebbe potuto suonare qualsiasi cosa dal suo passato, ma sta facendo qualcosa di piuttosto nuovo. Non era un concerto ambient scontato, era quasi, a mio avviso, come se Brian Eno si reinventasse come compositore classico moderno. L’ho ascoltato nello stesso modo in cui ascolto persone come John Luther Adams o Philip Glass. È stata una bellissima esibizione sinfonica d’atmosfera con molti musicisti che lavoravano e quasi ballavano, persino il direttore d’orchestra Kristjan Järvi. Mi è davvero piaciuto. È stato bello anche per me, perché mentre stavo camminando verso il teatro ho incontrato Richard Barbieri e ho finito per bere un drink con lui e farci una lunga chiacchierata per la prima volta da molto tempo.

Marco: Per concludere, anche se ne hai già parlato, quali sono i tuoi prossimi progetti? Un nuovo disco, alcuni live… e cos’altro?

Tim: Gli eventi più immediati in programma sono un paio di esibizioni dal vivo a gennaio. Ho anche fatto alcune sessioni per altri musicisti, incluso un artista italiano chiamato Stefano Panunzi, che fa parte della band Fjieri. Ho inciso delle parti vocali per lui, e un’altra per una band norvegese chiamata Laughing Stock, ed è stata davvero una bella sessione. Hanno un grande trombettista, norvegese. Sono molto vicino a finire il mio prossimo album solista, che, come ho detto, per la prima volta è interamente mio, quindi è molto diverso. Durerà circa 41 minuti con circa 17 tracce. Un lavoro davvero completamente diverso. Mi è piaciuto molto crearlo, e Steven, che lo ha mixato, è stato davvero incoraggiante e pensa che sia il mio miglior album, il che è fantastico. Ho anche fatto un paio di cose con Julianne Regan, che sono splendide. È una musicista molto creativa oltre che una grande cantante. Quindi ci sono parecchie cose che stanno accadendo o che stanno per essere pubblicate. E abbiamo anche discusso dell’idea di fare dal vivo The Album Years [il podcast creato da lui e da Steven Wilson, in cui trattano anno per anno le uscite musicali del passato, n.d.r.]. Abbiamo appena lanciato i nuovi episodi e ce ne sono molti altri in arrivo. Li abbiamo registrati per la prima volta faccia a faccia. Finalmente ci siamo incontrati nel post Covid e abbiamo parlato così a lungo che abbiamo prodotto dodici episodi in due giorni. E ci siamo visti di nuovo circa quattro giorni fa registrando due speciali di Natale. La Virgin Records sta ora promuovendo il podcast e potrebbe esserne coinvolta. Ci hanno parlato della possibilità di fare esibizioni dal vivo in cui discutiamo degli anni del passato [musicalmente parlando, n.d.r.] davanti al pubblico, o addirittura di intervistare alcune delle persone di cui discutiamo gli album. Quindi potrebbe essere molto divertente.

Marco: Grazie mille, Tim. È stato davvero bello vederti e parlare di tutto questo. Speriamo che ti sia piaciuta questa serata con noi e speriamo di rivederti presto! Ovviamente non vediamo l’ora di ricevere il box set e Swagger!

Tim: Beh, se riesci a farmi venire in Italia, ovviamente! Comunque grazie mille per le domande.

Cristina: Grazie, Tim, e buon Natale! Ciao!

Tim: Oh sì, buon Natale. Ci vediamo.

Cristina: In your opinion, what were the most important steps that allowed you to get signed to one little Indian at that time? Probably the cover of Donovan’s ‘Colors’? And also, why did you choose to cover this song from 1965?

Cristina: In your opinion, what were the most important steps that allowed you to get signed to one little Indian at that time? Probably the cover of Donovan’s ‘Colors’? And also, why did you choose to cover this song from 1965?